By Micah Friez

Published 2:51 p.m. on Aug. 15, 2023

Some heroes rightfully refuse to be lost to history.

More than 80 years after his death, John “Jack” McCormick still stands as one of the greatest athletes Bemidji has ever seen. But his status of immortality more heavily derives from his ultimate sacrifice in World War II and proud descendants who have faithfully upheld his legacy.

“We’ve heard stories about him our whole lives,” said Tom Henderson, McCormick’s great-nephew. “His legacy is important to all of us.”

Henderson, a 1982 Bemidji State University graduate, is one leaf on a big family tree that knows all about McCormick. Henderson is a third-generation BSU alum and an expert on McCormick’s abbreviated yet storied life.

Henderson returned to campus on Monday, Aug. 14, for the first time in years to give his daughter, Caroline, a tour. He tried to surprise her by showing her an old banner of McCormick that used to hang in the since-renovated Physical Education Complex, but it’s no longer on display. Yet, thanks to happenstance, the supposed dead-end was anything but.

In search of the banner, the two were directed across campus to the David Park House, which stores many of the old Hall of Fame plaques that have since been replaced in the Physical Education Complex. McCormick was an inaugural member of BSU’s Athletics Hall of Fame in 1978, and his plaque had floated around campus because administrators couldn’t track down any family members to whom they could bestow it.

Until Monday, it was housed in the office of Michael Herbert, a criminal justice professor who also authored the book "Leaving Campus: A World War II Epitaph," which chronicles the lives of McCormick and other former Bemidji State students who died while serving in World War II.

Familial ownership was restored on Monday. The Hendersons accepted an instantly treasured piece of family history by simply being in the right place at the right time.

“It was so emotional,” said Henderson, who lives in Victoria, Minn., but is in town visiting family on Lake Movil. “I had so much fun, especially because it wasn’t expected. It was just like, ‘Oh, I want to show her this banner.’ They said, ‘No, it’s not here. You should check the house up the street.’ … It was a lot of fun.”

As embodied by their determined journey, the memory of McCormick is still strong. Henderson’s mother, Pat, remembers her uncle for the tea parties he joined and the little red wagon he once gifted her. Undoubtedly, “he would have been a wonderful father,” she said.

Tom Henderson’s biggest tribute is through the naming of his son, John McCormick Henderson. And both bear a striking likeness to a worthy ancestor.

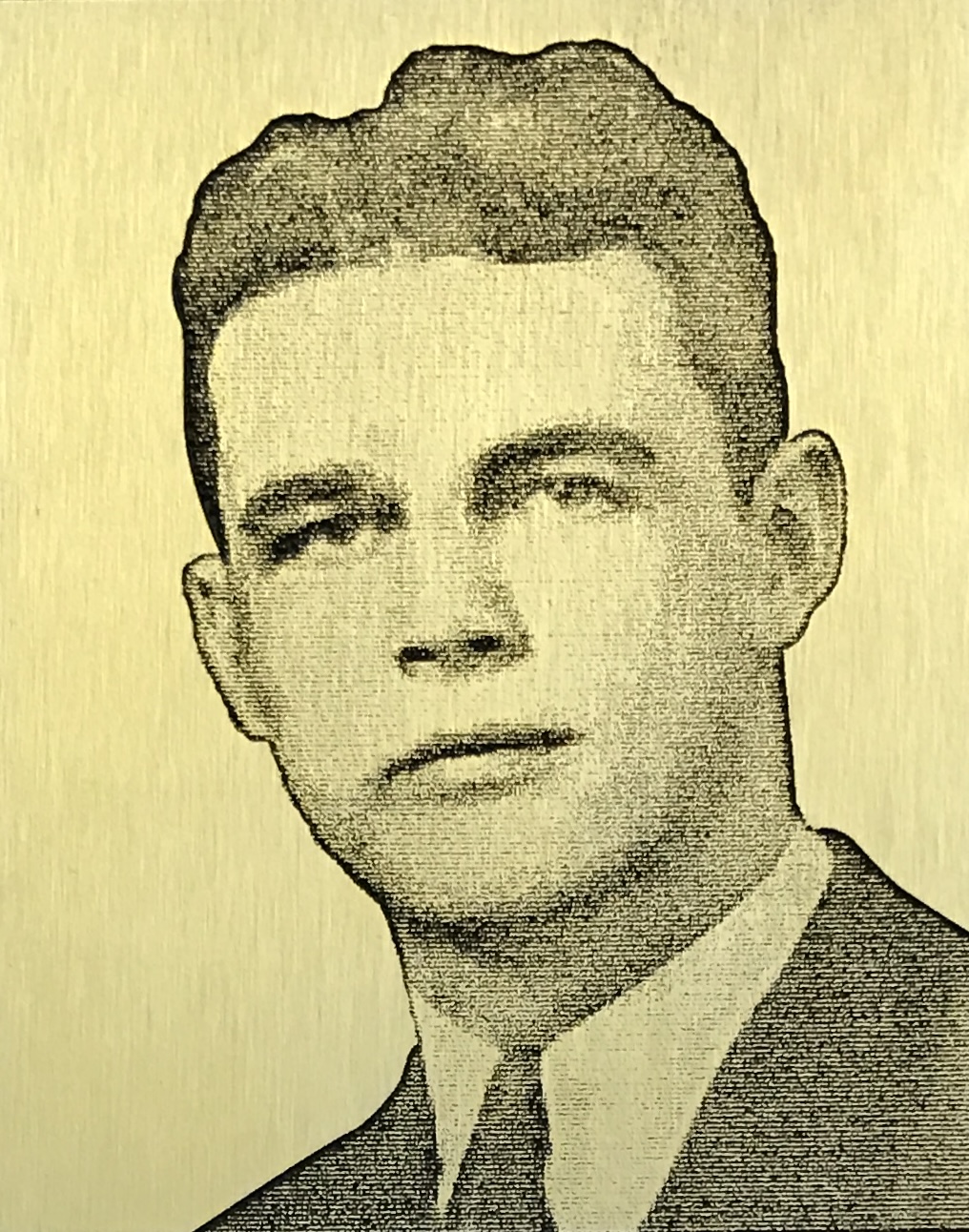

“When we saw the plaque, my daughter pointed out, ‘Gosh, there’s still a family resemblance, dad,’” Tom said. “My two brothers don’t look like me at all. They take from the other side of the family. But I look more like John McCormick. My son looks exactly like me, and one of my cousins looks exactly like me. It keeps popping through where it’s like, ‘Wow, that’s exactly like the McCormick side.’”

The success and service of Jack McCormick

McCormick was a star football and basketball player at both Bemidji High School and Bemidji State in the 1930s and 1940s, eventually posthumously joining the inaugural class in each school’s Hall of Fame.

Jack McCormick

During his senior year with the Lumberjacks, McCormick captained the football team to an unprecedented 7-0 record in 1935 and was the best defender on the basketball team’s first-ever state championship squad in 1936.

After graduating high school, McCormick donned the green and white at Bemidji State Teachers College. He was an all-conference player in both football and basketball, also helping the hoops reach the NAIA national tournament three times.

But while McCormick was under consideration for “big-time professional” football, World War II raged all facets of everyday American life. He sacrificed athletics and donned a new uniform, enlisting in the U.S. Air Force and training as a B-24 bomber pilot in the 67th Bomber Squadron and 44th Bombardment Group.

Grave news regrettably printed in the Feb. 22, 1943, edition of the Bemidji Daily Pioneer: “Word has been received here by Mrs. John McCormick from the war department that her son Lieut. Jack McCormick has been reported missing in action in the western European area since Feb. 16.”

McCormick died during a bombing mission in 1943 at just 24 years old. While co-piloting his B-24, named “Miss Marcia Anne,” over the English Channel, another aircraft malfunctioned and struck McCormick’s. Both planes burst into flames and plunged into the water. Another member of the squadron later journaled this tragic line about J.B. Long, McCormick’s co-pilot: “The man never had a chance.”

McCormick’s body was never found, but he has a gravesite in Bemidji and a memorial marker at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

He posthumously received a Purple Heart, awarded to those wounded or killed while serving their country, and it remains in the possession of the Henderson family. He was also one of the first Americans to receive an Air Medal, awarded for single acts of heroism while participating in aerial flight.

McCormick is one of 20 former Bemidji State students killed during World War II and yet, for many reasons, will forever be one of the greatest figures to ever pass through town.

“Bemidji gave up one of its best,” Henderson said.

Exlpore more

Bemidji Pioneer

Jack McCormick, one of Bemidji’s most successful athletes, did even more for his country

He captained an undefeated football team and was the best defender on a state championship basketball team at Bemidji High School. But his greatest accomplishment came by serving his country. Meet Jack McCormick, the Purple Lumberjack.

KEEP READING: