By The Bemidji Pioneer

Published 7:05 a.m. on Dec. 9, 2018

When winter temperatures descend at Bemidji State University, so can the students.

"I walked outside through the beginning of November, and now I just take the tunnels," said BSU freshman Abby Bowyer. "It's nice because I know it's only going to get colder. (The tunnels) are a perk."

The popular underground tunnel system at Bemidji State connects one end of campus to the other – aside from a frigid and often torturous outdoor walk between Tamarack and Linden Halls –leading to just about any and every indoor spot at the school.

Naturally, then, it's not uncommon for students to hike to classrooms in short sleeves and flip flops.

"It's super cool that you can walk to class in shorts and a T-shirt in 20 below," BSU freshman TJ Raden said. "If you have an 8 a.m., you can just roll out of bed at 7:40 and walk to class (without going outside). That's really nice."

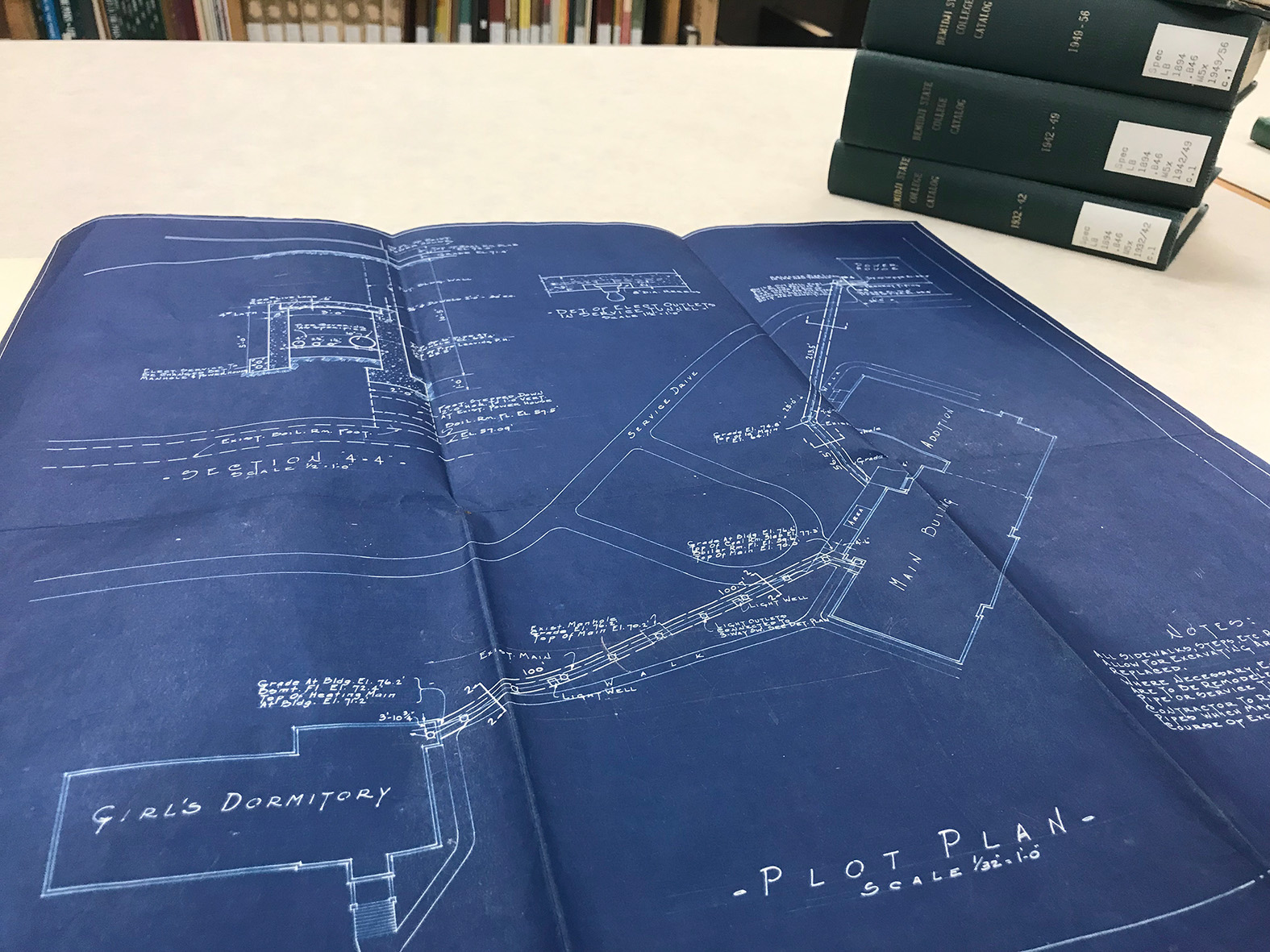

The university first broke ground on its tunnel system in 1935, when architect Nairne W. Fisher spearheaded a project for pipe tunnels to run below Bemidji State Teachers College. By 1941, the first underground walkway connected present day Deputy Hall and Memorial Hall, and three additional tunnels were completed by 1959.

The state Legislature in 1935 allowed $4,000 for the construction of the inaugural tunnel "to take care of underground water and steam mains, and gas and electric lines," former BSU history professor Art Lee wrote in his book "College In The Pines," which detailed the first 50 years of Bemidji State's history.

The original pipe tunnel plans detailed the wages, as well, and laborers earned between $0.35 and $1.20 an hour.

"Having a historical knowledge of the university is incredibly important, I think, to understand (what is) standing today and how certain aspects of the school became what they are," said Colleen Deel, who is in charge of the university archives at the A.C. Clark Library.

Two presidents oversaw the birth of the tunnel system. Manfred Deputy, the school's first president, and his successor, Charles Sattgast, both led the college during those days of digging.

"Deputy and Sattgast really shaped the way that BSU is today, even though they were around over 50 years ago," Deel said. "Between 1919 to 1964, there were only two presidents, and they really shaped the time for many, many decades, of what (the college) was."

Today, the intricate tunnel system stretches campus-wide. It can be more of a maze for inexperienced pedestrians.

"Me and my neighbor and my roommate, we took the weekends to figure them out. We got lost a few times," Bowyer said. "It took us about an hour to get over to the union. We got turned around a couple times. It was fun, but now I think I've got it down."

"At first it was kind of tough because it's just a new place," Raden added. "The academic side is where it gets kind of confusing. But once you get the hang of it, you're all right."

When the underground trek finally becomes familiar, the tunnels make for an amenity that isn't commonplace among other universities in the region.

"Whenever it's nice out, of course, I want to be outside," Deel said. "But the tunnels are wonderful for those icy, cold days. Who wouldn't want to use them? What's the point of braving the cold when you don't have to?"

And while deciding on a collegiate path can be confusing, the tunnel system made the trail a bit clearer for Bowyer.

"BSU is such a great school, but the fact that it is so far north can deter people," said Bowyer, who is originally from Watertown, Minn. "The tunnels are underground and they are a little bit warmer, which is what made me more OK with coming this far up north.

"It was the selling point, definitely, on my tour."

Written by Micah Friez

KEEP READING: