By Micah Friez

Published 3:25 p.m. on Nov. 22, 2023

Where were you on the night of Sept. 9, 1955?

Most Bemidjians have an alibi, but several safecrackers have a secret.

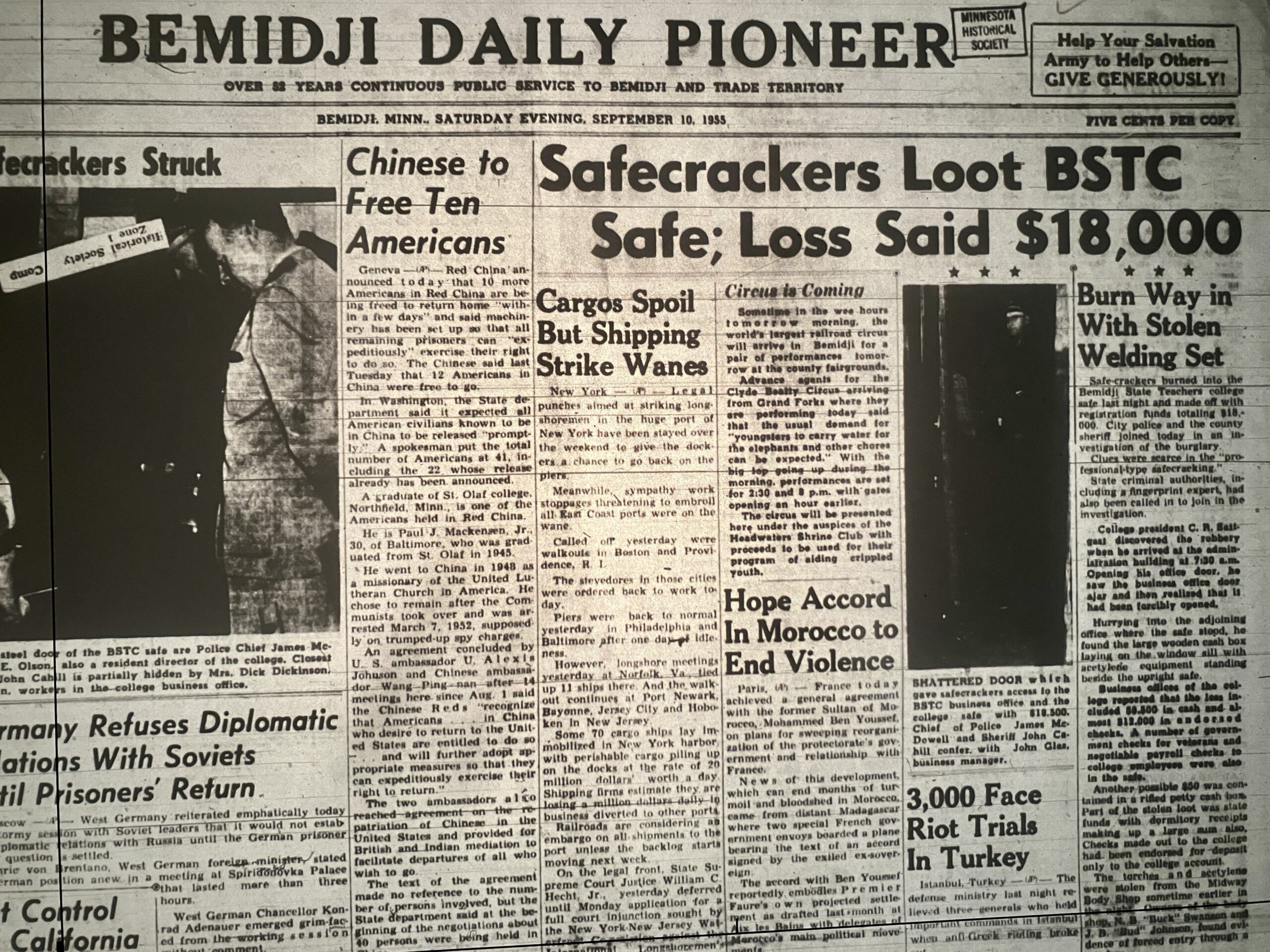

On that fateful Friday evening, burglars stormed Bemidji State Teachers College and made off with more than $18,000 in cash and checks – over $200,000 in today’s value – and successfully executed perhaps the biggest campus caper in school history.

From breaking and entering to cracking the safe to drowning evidence in a riverbed, here’s how the unidentified thieves got off scot free and coordinated a heist in Deputy Hall – and how BSTC still came out on top.

Sattgast and safecrackers

Charles Sattgast, the revered president of Bemidji State, had been in charge of the school since 1938. His passionate reputation went before him, and many believed he bled green and white – and that any nick on his finger would prove just that.

Under Sattgast, BSTC thrived. The campus expanded its borders from a 20-acre hub to a 74-acre kingdom with new buildings rising up all over. By 1955, the college had reached an all-time high in enrollment with 706 students, and this was the week of fall registration.

So, although Sept. 10, 1955, was a Saturday, it was no surprise that the dedicated Sattgast reported to work by 7:30 a.m.

Yet when he arrived at “The Main” (it wouldn’t be renamed Deputy Hall until 1959) an unsettling feeling overcame him. Sattgast noticed the business office door was ajar and, upon inspection, realized that it had been forcibly opened.

Hurrying into the adjoining office where the safe stood, he found the large wooden cash box lying empty on the window sill, plus welding equipment abandoned beside the vault. Stolen in the raid was $6,500 in cash and almost $12,000 in endorsed checks, mostly made up of student registration fees paid the day prior.

Immediately, Sattgast called the Beltrami County sheriff, who, along with local and state police, descended on the crime scene in search of clues.

Breadcrumbs were scarce, however, and the Northern Student described the operation as “a smoothly executed crime.” The Bemidji Daily Pioneer reported, “Sheriff John Cahill felt that the efficiency of the burglary suggested professional work, pointing to the hole burnt cleanly through the three-inch steel safe as one evidence of experienced safe-cracking.”

The looters left behind an acetylene torch, which they had stolen from an auto body shop across town earlier that night. Investigators also found numerous prints of nylon, suggesting the perpetrators wore gloves. Some fingerprints were left at the scene, but none of the results came back with conviction.

The clues didn’t reveal the bandits’ identities, but pieced together with outside intel, they did offer a glimpse into the inner workings of the master plan.

The timeline of the theft

Before the heist took place, another business in town got hit that night. Midway Body Shop fell victim to the scheme when the crew broke in and stole welding equipment. Shop owners N.B. “Buck” Swanson and J.B. “Bud” Johnson found evidence of forced entry through a window the next day.

Meanwhile, another accomplice had been patiently waiting inside The Main for hours. Sattgast believed a co-conspirator hid inside the building during the commotion of upperclassmen registration earlier that day.

“There are a hundred places where you can hide around the building,” Sattgast said in the aftermath.

Except for janitors, who regularly worked until 10 p.m., The Main was closed when Sattgast and Bemidji State business manager John Glas left the premises in the late afternoon for a meeting across campus.

After the custodians locked up for the evening, the coast was clear for nefarious conspiracies. The stowaway unlocked the doors and the crew operated undisturbed; the state didn’t provide BSTC with any night watchmen and nobody investigated the building during off hours, which Sattgast later lamented.

The looters removed bolts from the locked door to enter the business office, then attacked the vault with precision and emptied it of cash and checks.

“Clues were scarce in the ‘professional-type safecracking,’” the Daily Pioneer reported. “… The burglars did not take a burning tip for the torches from the body shop and since none was found at the scene, authorities surmised that the men had some of their own equipment.

“President Sattgast felt that the men involved were familiar with the building. He revealed that had the burglars struck on Thursday night, after the even-heavier freshman registration, they would have found $18,000 in cash in the safe.”

After getting their hands on the money, the bandits ran south. They abandoned $4,000 worth of uncashable checks by dumping them into the Crow Wing River near Motley. (Glas explained that all the checks were already endorsed for deposit into the college account only, so the thieves wouldn’t be able to pocket the money for themselves.) A group of boys, thinking it was a tackle box floating on the river, discovered the loot on Sunday evening and reported it to local authorities.

The sheriff and the chief of police traveled down to chase the new lead. But the thieves were already in the wind, complete with $6,500 in cash as an ample consolation prize.

Finding fortune

Several weeks after the heist, official investigators expressed “little hope” for the recovery of the money, and they doubted the looters would make an attempt to cash the still-missing checks since they were already endorsed to Bemidji State.

But the college came out unscathed. The vault and all its contents were fully covered by insurance, so BSTC suffered no financial loss.

The bigger pot of money that Sattgast mentioned – $18,000 cash from the registration of Thursday’s record-setting freshman class – had already been banked before the thieves showed up.

Bemidji State marched on prosperously. The 1955-56 academic year marked the second of what became 17 consecutive record-breaking enrollment years through 1970-71. The college grew exponentially, continuing to establish and broaden its footprint in northern Minnesota for thousands of students.

Even a few dollars richer, it’s impossible to say whether the swindlers were ever so fortunate.